I offer Breathwork Facilitation to select clients.

Breathwork is a simple, yet powerful discipline that uses conscious circular breathing and the presence of a trained facilitator for deep inner healing and moving beyond the grip of personality fixations that I offer to select clients. I had over seven years of training in Integrative Breathwork with Inspiration Consciousness School.

Breath is tied to our emotional, mental, and physical states, so through making an automatic and largely unconscious process of breathing intentional and conscious, Breathwork brings the imprint of years of undigested psychological material to the surface, where it can be safely processed. A full session requires working with a trained practitioner, individually or in a group.

“By voluntarily changing the rate, depth, and pattern of breathing, we can change the messages being sent from the body’s respiratory system to the brain. In this way, breathing techniques provide a portal to the autonomic communication network through which we can, by changing our breathing patterns, send specific messages to the brain using the language of the body, a language the brain understands and to which it responds. Messages from the respiratory system have rapid, powerful effects on major brain centers involved in thought, emotion, and behavior.” -The Healing Power of Breath, Richard Brown, M.D. and Patricia Gerbarg, M.D. (2012) p. 35

This simple style of breathing, at minimum, can help release stress and tension, providing restorative effects of clear-mindedness, increased energy, and an improved sense of well-being; yet when partnered with an experienced practitioner, a session can become incredibly intense. Depending on the individual and where a person is in their process, experiences can vary from emotional catharsis, profound openings to archetypal or mystical experiences, or one may work through deeply traumatic past experiences to find the freedom on the other side. Healthy, full breathing vitalizes the nervous system, expands our capacity for sensation, and helps us release stress and trauma that may be pent-up in our bodies.

My first breathwork session profoundly changed my life. I wouldn’t have believed such a simple adjustment of breathing could have such powerful effects.

Because breath is the only function of our Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) that we can consciously control, and because the depth and rate of breath change along with emotional states, a great deal of emotional and other unconscious content is deeply tied to the breath and therefore able to be raised to awareness and released by the breath. Breathing properly, with a greater depth of full belly breaths and a steady rate, begins to bring the two branches of the ANS into balance.

People unconsciously use the awareness-limiting effects of shallow breathing as a kind of psychological “armoring” against allowing the brunt of troubling psychological content to rise to one’s awareness; essentially, it’s a way of blocking consciousness and dulling painful experiences. Years, even decades, of poor self-regulation has meant that our capacity to tolerate states of high nervous system arousal is typically deeply deficient. A narrow range of tolerance intensifies difficulties we may experience in confronting, metabolizing, and healing from trauma, keeping it frozen in the body, and this limited bandwidth. This makes us prone to be easily overwhelmed physiologically, emotionally, and mentally, which we deal with by acting out the negative patterns of our Enneagram Type. It’s not only negative experiences that our energy is mobilized in resistance to. We also resist vulnerability, joy, softness of heart, and love. No matter our type and temperament, nearly everyone in the modern world employs a collection of artificial breath-restrictive tendencies.

Breath is inextricably tied to sensation and is necessary for conscious self-regulation. Conscious breath is the most reliable doorway to greater sensation and provides the best support in staying anchored into physical sensation, the foundation of presence. Without awareness of breath, we are prone to forget to sense ourselves. Ongoing awareness of breath is also a powerful focal point in anchoring ourselves in presence amidst powerful emotions, the emergence of painful memories, and as we experience changes and challenges to our identity.

Breathing practices have a long-standing role in spiritual traditions all over the world. In many different languages, the words for spirit and soul are etymologically linked to breath, a statement to the crucial importance of breath in spiritual work. The English word “spirit” is derived from the Latin word spiritus, which means “breath,” while the Latin word for soul, anima, also derives from a word meaning “breath.” The Arabic word for spirit, Ruh, is related to the Hebrew word for Holy Spirit, Ruach, and it also means "breath"; and the Arabic “Nafs” means breath, which also refers to the “lower soul” or ego.

In Buddhism, Anapanasati is a central meditation practice that focuses solely on witnessing the breath and sensation without modifying it. It means, simply, “mindfulness of breath.” In the Maha Rahulovada Sutta, the Buddha says to his son, Rahula, “This is the practice of mindfulness of breath, Rahula. This is how the sincere practice of mindfulness of breath is of great fruit, of great benefit. If mindfulness of breath is practiced continuously, then your last breath will be in knowing, not in unknowing.”

A core Sufi practice is that of dhikr. Dhikr, meaning “remembrance,” encompasses a great deal, but is centered on the inward recitation of mantras or prayers linked to the breath to stabilize attention on the divine. A Sufi source that J. G. Bennett viewed as a major influence on the groups that Gurdjieff trained in, the Khwajagan “Masters of Wisdom,” greatly emphasized the primacy of conscious breathing to their practice. The Sufi Master Khwaja Abd al-Khaliq Ghujdawani articulated eight of what later came to be eleven aphorisms taken as “rules,” or precepts, of the Khwajagan, later absorbed by the Naqshbandi Order. The first expression of the “Way of the Masters” is Hosh Dar Dam, in Persian. According to Bennett (1980),

[t]his can be translated “breath consciously.” The Persian word hosh is almost the same as the Greek nepsis - in Latin sobrietas - used eight centuries earlier by the Masters of the Syrian desert and which appears very often in the Philokalia, a work that Ouspensky attributed to the Masters of Wisdom. He regarded this term as equivalent to Gurdjieff’s “self-remembering”. As used by the Khwajagan, it is always connected with breathing. According to their teaching the air we breathe provides us with food for the second or spirit body, called by Gurdjieff the kesdjan body from two Persian words meaning the “vessel of the spirit”...

Hosh Dar Dam, conscious breathing, was regarded as the primary technique for self-development. The Rashahat says that the meaning of hosh dar dam is that breathing is the nourishment of the inner man… Khwaja Baha ad-din Naqshband said: “In this path, the foundation is built on breathing. The more that one is able to be conscious of one’s breathing, the stronger is one’s inner life (p. 135).

See “About Me & Testimonials” page for client’s experiences. Breathwork facilitation can be done online, but I require a minimum of three talk session so that the client and I can build trust and have a shared sense of one another’s inner landscape. I am very selective of who I offer breathwork to and screen for a variety of factors.

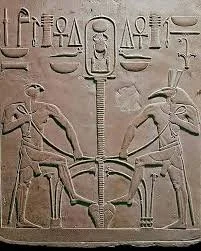

The Sema-Tawy, “The Union of the Two Lands”, an image representing the union of Lower and Upper Egypt, symbolizing the unification of spiritual and material worlds. The “Sema” hierogylph is the lungs and trachea, meaning “union”, signifying that breath cultivates a relationship between essence and personality.